Matrix Representation

Periodically, the question arises: does Panda store matrices in column-major or row-major format? Unfortunately, people who ask that question often fail to realize that there are four ways to represent matrices, two of which are called “column major,” and two of which are called “row major.” So the answer to the question is not very useful. This section explains the four possible ways to represent matrices, and then explains which one panda uses.

The Problem

In graphics, matrices are mainly used to transform vertices. So one way to write a matrix is to write the four transform equations that it represents. Assuming that the purpose of a matrix is to transform an input-vector \(\begin{pmatrix}x_i&y_i&z_i&w_i\end{pmatrix}\) into an output vector \(\begin{pmatrix}x_o&y_o&z_o&w_o\end{pmatrix}\), the four equations are:

There are two different orders that you can store these coefficients in RAM:

Storage Option 1: A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H,J,K,L,M,N,O,P,Q

Storage Option 2: A,E,J,N,B,F,K,O,C,G,L,P,D,H,M,Q

Also, when you’re typesetting these coefficients in a manual (or printing them on the screen), there are two possible ways to typeset them:

A B C D

E F G H

J K L M

N O P Q

Typesetting

Option 1

|

A E J N

B F K O

C G L P

D H M Q

Typesetting

Option 2

|

These are independent choices! There is no reliable relationship between the order that people choose to store the numbers, and the order in which they choose to typeset them. That means that any given system could use one of four different notations.

So clearly, the two terms “row major” and “column major” are not enough to distinguish the four possibilities. Worse yet, to my knowledge, there is no established terminology to name the four possibilities. So the next part of this section is dedicated to coming up with a usable terminology.

The Coefficients are Derivatives

The equations above contain sixteen coefficients. Those coefficients are derivatives. For example, the coefficient “G” could also be called “the derivative of \(y_o\) with respect to \(z_i\).”

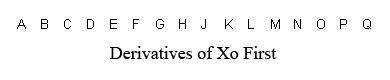

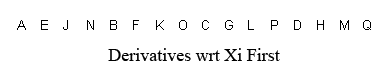

This gives us a handy way to refer to groups of coefficients. Collectively, the coefficients “A,B,C,D” could also be called “the derivatives of \(x_o\) with respect to \(\begin{pmatrix}x_i&y_i&z_i&w_i\end{pmatrix}\)” or just “the derivatives of \(x_o\)” for short. The coefficients “A,E,J,N” could also be called “the derivatives of \(\begin{pmatrix}x_o&y_o&z_o&w_o\end{pmatrix}\) with respect to \(x_i\)” or just “the derivatives with respect to \(x_i\)” for short.

This is a good way to refer to groups of four coefficients because it unambiguously names four of them without reference to which storage option or which typesetting option you choose.

An alternative that works just as well (and is usually the only way to reverse-engineer a document that was written without specifying these conventions) is to find the translation parts of the matrix. If the translation lives in the rightmost column, then the matrix is intended for column vectors on the right. If the translation lives in the bottom row, then the matrix is intended for row vectors on the left.

What to Call the Two Ways of Storing a Matrix

So here, again, are the two ways of storing a matrix. But using this newfound realization that the coefficients are derivatives, I have a meaningful way to name the two different ways of storing a matrix:

In the first storage scheme, the derivatives of \(x_o\) are stored first. In the second storage scheme, the derivatives with respect to \(x_i\) are stored first.

What to Call the Two Ways of Printing a Matrix

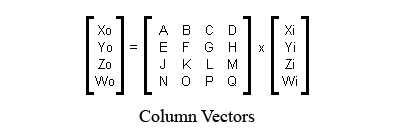

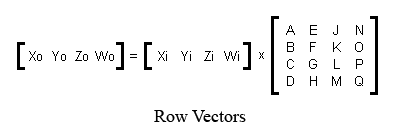

One way to write the four equations above is to write them out using proper mathematical notation. There are two ways to do this, shown below:

Notice that the two matrices shown above are laid out differently. The first layout is the appropriate layout for use with column vectors. The second layout is the appropriate layout for use with row vectors. So that gives me a possible terminology for the two different ways of typesetting a matrix: the “row-vector-compatible” notation, and the “column-vector-compatible” notation.

The Four Possibilities

So now, the four possible representations that an engine could use are:

Store derivatives of \(x_o\) first, typeset in row-vector-compatible notation.

Store derivatives of \(x_o\) first, typeset in column-vector-compatible notation.

Store derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first, typeset in row-vector-compatible notation.

Store derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first, typeset in column-vector-compatible notation.

The Terms “Column Major” and “Row Major”

The term “row-major” means “the first four coefficients that you store, are also the first row when you typeset.” So the four possibilities break down like this:

Store derivatives of \(x_o\) first, typeset in row-vector-compatible notation (COLUMN MAJOR)

Store derivatives of \(x_o\) first, typeset in column-vector-compatible notation (ROW MAJOR)

Store derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first, typeset in row-vector-compatible notation (ROW MAJOR)

Store derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first, typeset in column-vector-compatible notation (COLUMN MAJOR)

That makes the terms “row major” and “column major” singularly useless, in my opinion. They tell you nothing about the actual storage or typesetting order.

Panda Notation

Now that I’ve established my terminology, I can tell you what panda uses. If

you examine the panda source code, in the method LMatrix4f::xform, you will

find the four transform equations. I have simplified them somewhat (ie,

removed some of the C++ quirks) in order to put them here:

#define VECTOR4_MATRIX4_PRODUCT(output, input, M) \

output._0 = input._0*M._00 + input._1*M._10 + input._2*M._20 + input._3*M._30; \

output._1 = input._0*M._01 + input._1*M._11 + input._2*M._21 + input._3*M._31; \

output._2 = input._0*M._02 + input._1*M._12 + input._2*M._22 + input._3*M._32; \

output._3 = input._0*M._03 + input._1*M._13 + input._2*M._23 + input._3*M._33;

Then, if you look in the corresponding header file for matrices, you will see the matrix class definition:

struct {

FLOATTYPE _00, _01, _02, _03;

FLOATTYPE _10, _11, _12, _13;

FLOATTYPE _20, _21, _22, _23;

FLOATTYPE _30, _31, _32, _33;

} m;

So this class definition shows not only how the coefficients of the four equations are stored, but also the layout in which they were intended to be typeset. So from this, you can see that panda stores derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first, and it typesets in row-vector-compatible notation.

Interoperability with OpenGL and DirectX

Panda is code-compatible with both OpenGL and DirectX. All three use the same storage format: derivatives wrt \(x_i\) first. You can pass a panda matrix directly to OpenGL’s “glLoadMatrixf” or DirectX’s “SetTransform”.

However, remember that typesetting format and data storage format are independent choices. Even though two engines are interoperable at the code level (because their data storage formats match), their manuals might disagree with each other (because their typesetting formats do not match).

The panda typesetting conventions and the OpenGL typesetting conventions are opposite from each other. The OpenGL manuals use a column-vector-compatible notation. The Panda manuals use a row-vector-compatible notation.

DirectX uses the same conventions as Panda for both typesetting and memory storage: row vectors on the left, row major storage with the translation in the bottom row.