Multithreaded Render Pipeline

As of Panda3D version 1.8, Panda supports a multithreaded render pipeline for optimal performance on multiprocessor machines. If your computer has at least two CPU cores (for instance, because you have a dual-core or quad-core CPU), then you can direct Panda to utilize up to three different CPU cores for rendering the scene, which can lead to a theoretical performance improvement of up to 3 times faster than a simple single-CPU approach. (In practice, an improvement of 3x is rare; improvements of 1.5x to 2x are far more common.)

This feature isn’t enabled all the time, partly because it is still somewhat new and experimental, and partly because it is not always the best idea to enable this feature, depending on your precise needs.

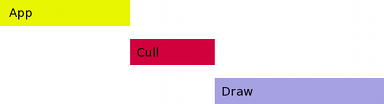

To use this feature successfully, you will need to understand something about how it works. First, consider Panda’s normal, single-threaded render pipeline. The time spent processing each frame can be subdivided into three separate phases, called “App”, “Cull”, and “Draw”:

In Panda’s nomenclature, “App” is any time spent in the application yourself, i.e. your program. This is your main loop, including any Python code (or C++ code) you write to control your particular game’s logic. It also includes any Panda-based calculations that must be performed synchronously with this application code; for instance, the collision traversal is usually considered to be part of App.

“Cull” and “Draw” are the two phases of Panda’s main rendering engine. Once your application code finishes executing for the frame, then Cull takes over. The name “Cull” implies view-frustum culling, and this is part of it; but it is also much more. This phase includes all processing of the scene graph needed to identify the objects that are going to be rendered this frame and their current state, and all processing needed to place them into an ordered list for drawing. Cull typically also includes the time to compute character animations. The output of Cull is a sorted list of objects and their associated states to be sent to the graphics card.

“Draw” is the final phase of the rendering process, which is nothing more than walking through the list of objects output by Cull, and sending them one at a time to the graphics card. Draw is designed to be as lightweight as possible on the CPU; the idea is to keep the graphics command pipe filled with as many rendering commands as it will hold. Draw is the only phase of the process during which graphics commands are actually being issued.

You can see the actual time spent within these three phases if you inspect your program’s execution via the PStats tool. Every application is different, of course, but in many moderately complex applications, the time spent in each of these three phases is similar to the others, so that the three phases roughly divide the total frame time into thirds.

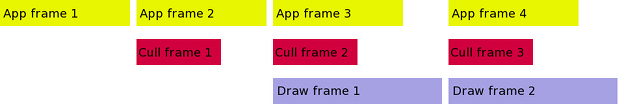

Now that we have the frame time divided into three more-or-less equal pieces, the threaded pipeline code can take effect, by splitting each phase into a different thread, so that it can run (potentially) on a different CPU, like this:

Note that App remains on the first, or main thread; we have only moved Cull and Draw onto separate threads. This is important, because it means that all of your application code can continue to be single-threaded (and therefore much easier and faster to develop). Of course, there’s also nothing preventing you from using additional threads in App if you wish (and if you have enough additional CPU’s to make it worthwhile).

If separating the phases onto different threads were all that we did, we wouldn’t have accomplished anything useful, because each phase must still wait for the previous phase to complete before it can proceed. It’s impossible to run Cull to figure out what things are going to be rendered before the App phase has finished arranging the scene graph properly. Similarly, it’s impossible to run Draw until the Cull phase has finished processing the scene graph and constructing the list of objects.

However, once App has finished processing frame 1, there’s no reason for that thread to sit around waiting for the rest of the frame to be finished drawing. It can go right ahead and start working on frame 2, at the same time that the Cull thread starts processing frame 1. And then by the time Cull has finished processing frame 1, it can start working on culling frame 2 (which App has also just finished with). Putting it all in graphical form, the frame time now looks like this:

So, we see that we can now crank out frames up to three times faster than in the original, single-threaded case. Each frame now takes the same amount of time, total, as the longest of the original three phases. (Thus, the theoretical maximum speedup of 3x can only be achieved in practice if all three phases are exactly equal in length.)

It’s worth pointing out that the only thing we have improved here is frame throughput–the total number of frames per second that the system can render. This approach does nothing to improve frame latency, or the total time that elapses between the time some change happens in the game, and the time it appears onscreen. This might be one reason to avoid this approach, if latency is more important than throughput. However, we’re still talking about a total latency that’s usually less than 100ms or so, which is faster than human response time anyway; and most applications (including games) can tolerate a small amount of latency like this in exchange for a smooth, fast frame rate.

In order for all of this to work, Panda has to do some clever tricks behind the scenes. The most important trick is that there need to be three different copies of the scene graph in different states of modification. As your App process is moving nodes around for frame 3, for instance, Cull is still analyzing frame 2, and must be able to analyze the scene graph before anything in App started mucking around to make frame 3. So there needs to be a complete copy of the scene graph saved as of the end of App’s frame 2. Panda does a pretty good job of doing this efficiently, relying on the fact that most things are the same from one frame to the next; but still there is some overhead to all this, so the total performance gain is always somewhat less than the theoretical 3x speedup. In particular, if the application is already running fast (60fps or above), then the gain from parallelization is likely to be dwarfed by the additional overhead requirements. And, of course, if your application is very one-sided, such that almost all of its time is spent in App (or, conversely, almost all of its time is spent in Draw), then you will not see much benefit from this trick.

Also, note that it is no longer possible for anything in App to contact the graphics card directly; while App is running, the graphics card is being sent the drawing commands from two frames ago, and you can’t reliably interrupt this without taking a big performance hit. So this means that OpenGL callbacks and the like have to be sensitive to the threaded nature of the graphics pipeline. (This is why Panda’s interface to the graphics window requires an indirect call: base.win.requestProperties(), rather than base.win.setProperties(). It’s necessary because the property-change request must be handled by the draw thread.)

Enabling the Multithreaded Render Pipeline

To enable this feature, simply set the following variable in your Config.prc file:

threading-model Cull/Draw

The names “Cull” and “Draw” in the above are used as the names of the threads that serve Cull and Draw, respectively. It doesn’t matter what you call them; the name before the slash will be the name of the thread that performs Cull, and the name following the slash will be the name of the thread that performs Draw. (So setting this to Draw/Cull will not reverse the phases, but will instead just give your two threads very misleading and confusing names.)

The above string defines a different thread for each of App, Cull, and Draw. You can also assign these three phases to threads in different ways:

threading-model /Draw

Creates a two-thread model: assigns App and Cull together on the main thread, and puts Draw on its own thread. This is most appropriate when the total amount of time for App + Cull in your application is similar to the total amount of time for Draw.

threading-model Cull/Cull

threading-model Cull

These two are equivalent and create a different two-thread model: App is on its own thread, and Cull and Draw are together on a separate thread. This is most appropriate when the total amount of time for App in your application is similar to the total amount of time for Cull + Draw.

More generally, the threading model defines the names of the two threads that serve Cull and Draw. A slash separates the two phases. If the thread name for either phase is the empty string, then the name is understood to be the same name as the previous phase (or the App phase for the first one). If two threads have the same name, they refer to the same thread, so “Cull/Cull” means to place both Cull and Draw on the same thread, named “Cull”. The specific name is irrelevant; it could have been called “Foo/Foo” just as easily.